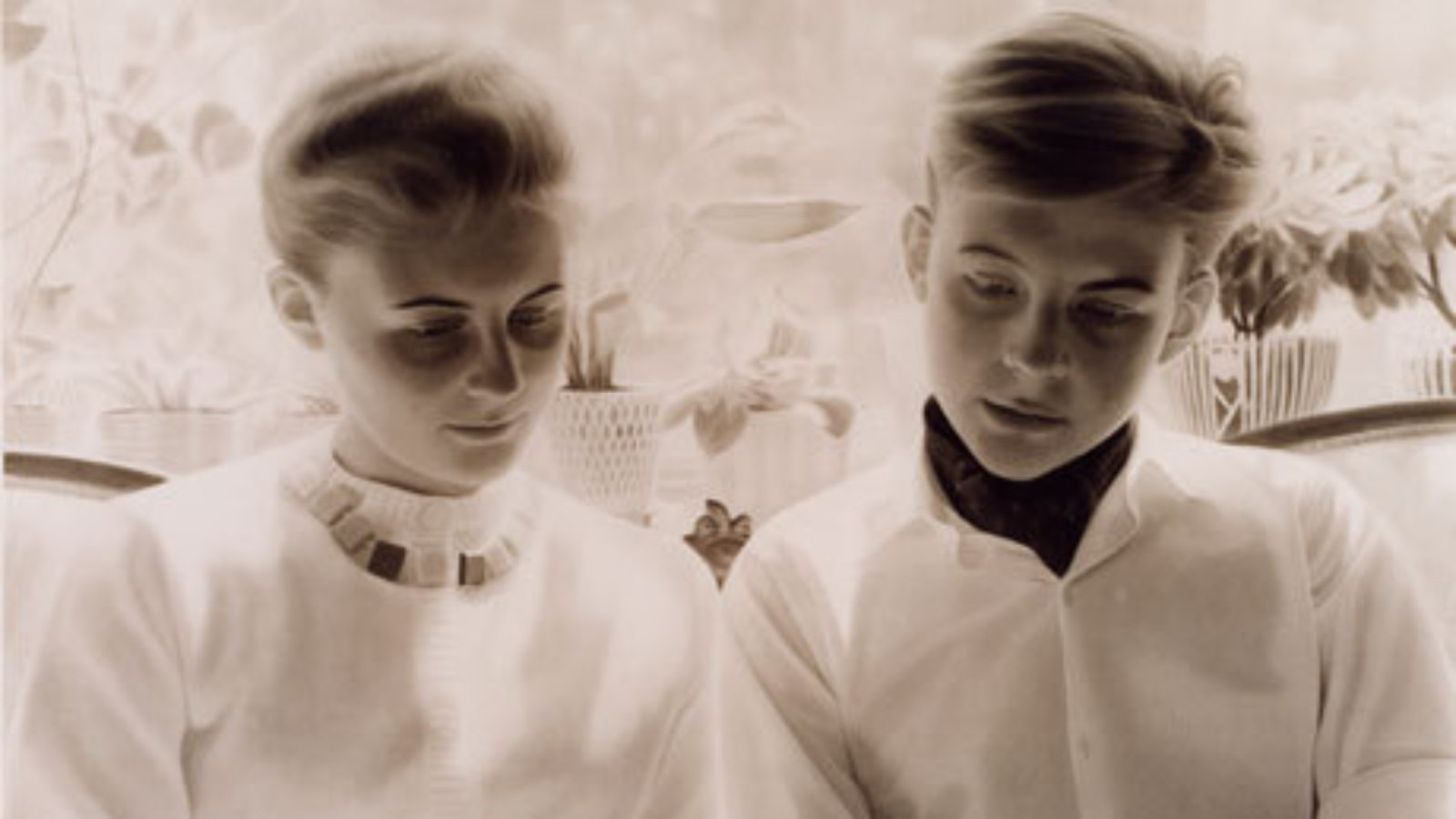

Over the course of the past four decades, the exhibition series Tendenser (Tendencies) has been held at the Galleri F15. The purpose of this ongoing project is to gather together the most recent, inventive craft work in the Nordic Countries. Curator for the 40th edition of Tendenser is Glenn Adamson, head of research at the Victoria and Albert Museum and tutor at the Royal College of Art. Photo: By the Window, 2003-2004. Gunnel Wahlstrand. Private Collection. Photgraph Björn Larsson.

Artists

Gunnel Wåhlstrand(SE),Mia E Göransson(SE),Marie Torbensdatter Hermann(DK),Karina Nøkleby Presttun (NO),Caroline Slotte(SE),Fredrik Ingemansson(SE),Pernille Braun (DK) Nicolas Cheng SE/Beatrice Bovia(IT/SE),Hanna Hedman(SE)/Sanna Lindberg(SE),Maja Gunn(SE),Miro Sazdic Löwstedt(SE).

Tenderness

Curator’s Statement by Glenn Adamson

When I was invited to curate the 40th anniversary installment of the Tendenser series at Galleri F15, I immediately spotted my chance to do something I’d been wanting to try. I’ll admit right off that part of my reaction had to do with curating for an institution far from home, a plane trip away from most of my professional colleagues. Tenderness is, for me, a very personal project: a show with my heart openly displayed on its sleeve. This is something I simply have never tried before. I have dropped my usual guard, and to be as honest as I can be about what moves me. Usually, curators indicate what they think is “interesting” from a position of Olympian detachment, and I would include myself in that generalization. Just this once, I wanted to give in to romanticism.

Beyond the curiosity of trying something new, I had a few particular reasons to make a show about tenderness. When I got the invitation from Galleri F15, back in 2011, I’d just finished curating a major exhibition about Postmodernism. That meant spending four years with the chilly ironies and strident exaggerations of the 1980s. There was scarcely a deeply felt object in sight. By the end of it, I was desperate to think about art that was more yielding, and more earnestly inviting.

Then there was my gradual intellectual rapprochement with the Arts and Crafts Movement. This episode in craft history had always functioned for me as a sort of obstacle course – an impressive array of positions that I could try to critique, evade and subvert. Though I have been a specialist on craft for a long time, I have never simply been “for” it. In this sense, I have consciously departed from the example of figures like John Ruskin, who thought of hand skill as a remedy for the ails of modern life, finding in it an affective quality (that is, an expression of deep humanness) which was depressingly lacking in factory spaces and the mass-produced objects made in them. I have similarly positioned myself against William Morris, who articulated a social project based on craft and the ‘joy in labour’ it supposedly engendered.

While according these great figures the respect they deserve, I have always been motivated to explore the other things craft has been and can be. I have often employed deconstructive and feminist strategies, which help to show how craft ‘works’ as a negative image, a site of strategic repression within fine art and other areas of dominant culture. Equally, I have been attracted to arguments that contradict Ruskin and Morris’ accounts of modern production. I have tended to stress the work of industrial artisans, who were more or less ignored by Arts and Crafts idealists, and also to point out the laborious and exploitative aspects of supposedly joyful production. When Galleri F 15 came calling, I was in the midst of writing a new book called The Invention of Craft which sets out this revisionist case. Its last chapter is an analysis of the ‘memory work’ of the Arts and Crafts Movement, which discusses its omissions and displacements as symptoms of the trauma of modernity.

With all that going on in my head, a show on Tenderness began to feel like a downright obligation. After all, no amount of theorization or historical argument will change the fact that craft is indeed ‘affective’ and, often, brings joy to the world. People feel deeply about craft, its humane qualities, its poignancy. I have always known this and have never been immune to the feeling myself; many is the time a handmade pot has stirred my soul. The fact that I can contextualize this response, seeing in it a deep-seated cultural training dating back to the nineteenth century, doesn’t do away with the instinct.

And so, in this project, I decided finally to face up to my own private feelings about craft – as opposed to my public thoughts about it. Though I might have done this anywhere, the stipulation that I could include only artists from Nordic countries helped me a great deal. From the outside perspective of an American living in the UK, the politics of generosity in this part of the world seem nearly utopian; and the ‘soft modernism’ of Scandinavian design seems a visualization of that state of affairs. I was interested to test these superficial stereotypes (I realize that is all they are) against the reality of contemporary production.

In accepting the commission to curate the show, I knew that I had always been given the warmest of welcomes from colleagues here in Scandinavia – at institutions like the Gustavsberg Konsthall and IASPIS in Sweden, the Kunstindustrimuseum in Denmark, and in art schools and museums in Norway itself – and that I had several dear friends who are craft artists from this part of the world. I make no apology for including the work of people that I care about. For me, that is all part of the story of the show.

In the end, I learned a great deal about tenderness from these friends, and the other artists whom I met while working on the project. To be perfectly frank, I was ready to relent on my usual critical faculties to get the emotional tone that I wanted. In practice, that was completely unnecessary. Once I had opened myself up to the full range of emotions contained in these artists’ works, I discovered how rich and complex the possibilities could be. In the exhibition you see tenderness given a range of material expression: the delicacy of certain forms, materials, and colors (quite a bit of pink); images of youth giving way to age; the way that attention can catch on a stray object and linger there. Craft is present throughout, though not in the way some viewers might expect. I have included a painting (admittedly, an immaculately skillful one), photographs (in which handmade jewellery and garments are used as props), film, sound, and scent as part of the scenography. My hope is that visitors will experience craft not a set of particular disciplines, but more as a gentle ambiance pervading the exhibition space.

A final ingredient in the project is the site, Galleri F 15 itself. Even someone who has never visited before will immediately grasp that this beautiful estate is saturated with memories. Some of these dates back centuries and seem to have settled in the corners of the galleries, with their ancient ceramic ovens. Other memories have accumulated since the building opened as a public gallery in 1966. And of course, the previous 39 exhibitions in the Tendenser series also populate these rooms as a presiding host of benevolent ghosts. I hope that Tenderness does some justice to that past. For me, it serves as an affirmation that craft is, when all is said and done, very much worthy of my love as I move into the future.